Of Men and Dogs

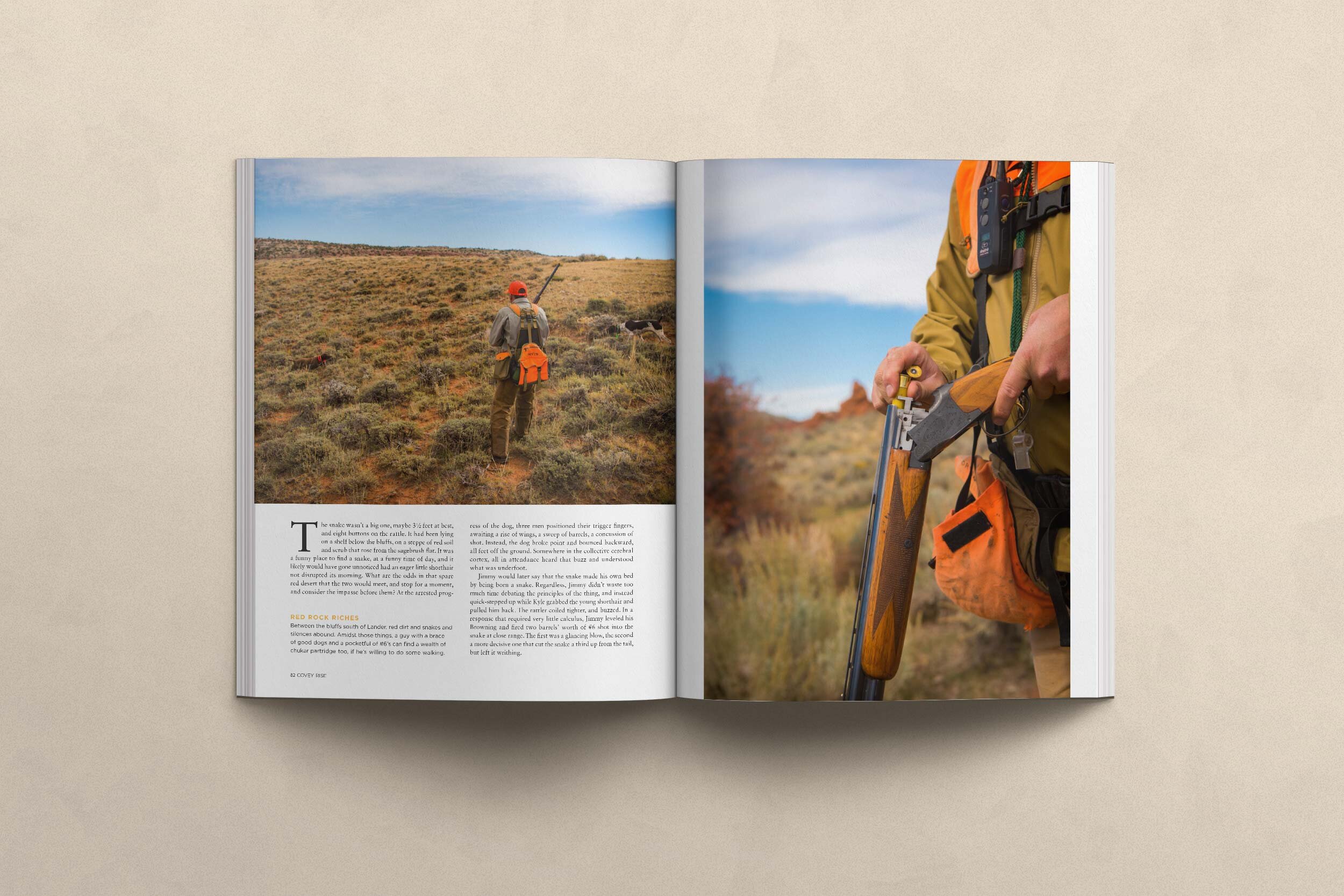

The snake wasn’t a big one, maybe 3 and a half feet at best, and 8 buttons on the rattle. It had been laying on a shelf below the bluffs, on a steppe of red soil and scrub that rose from the sagebrush flat. It was a funny place to find a snake, at a funny time of day, and it likely would have gone unnoticed had an eager little shorthair not disrupted its morning. What are the odds in that spare red desert that the two would meet, and stop for a moment, and consider the impasse before them? At the arrested progress of the dog, three men positioned their trigger fingers, awaiting a rise of wings, a sweep of barrels, a concussion of shot. Instead, the dog broke point and bounced backward, all feet off the ground. Somewhere in the collective cerebral cortex, all in attendance heard that buzz and understood what was underfoot.

Jimmy would later say that the snake made his own bed by being born a snake. Regardless, Jimmy didn’t waste too much time debating the principles of the thing, and instead quick-stepped up while Kyle grabbed the young shorthair and pulled him back. The rattler coiled tighter, and buzzed. In a response that required very little calculus, Jimmy leveled his Browning and fired two barrels’ worth of number 6 shot into the snake at close range. The first was a glancing blow, the second a more decisive one that cut the snake a third up from the tail, but left it writhing. Grossenbacher, altogether nonplussed by the whole affair and never one to campaign for snakes anyhow, insisted that Jimmy finish the job. One more shot and the ordeal was ended, and none too soon: the young shorthair had wrenched free of Kyle’s grasp and moved on, locking up on point not fifty yards ahead. While Kyle and Jimmy fumbled to close guns and negotiate the hillside, Grossenbacher waited for the snake to stop squirming, put a boot on his head, and cut off the rattle. He put it in his left breast pocket, where it continued to quiver. Such a treasure… his daughter would be thrilled.

*

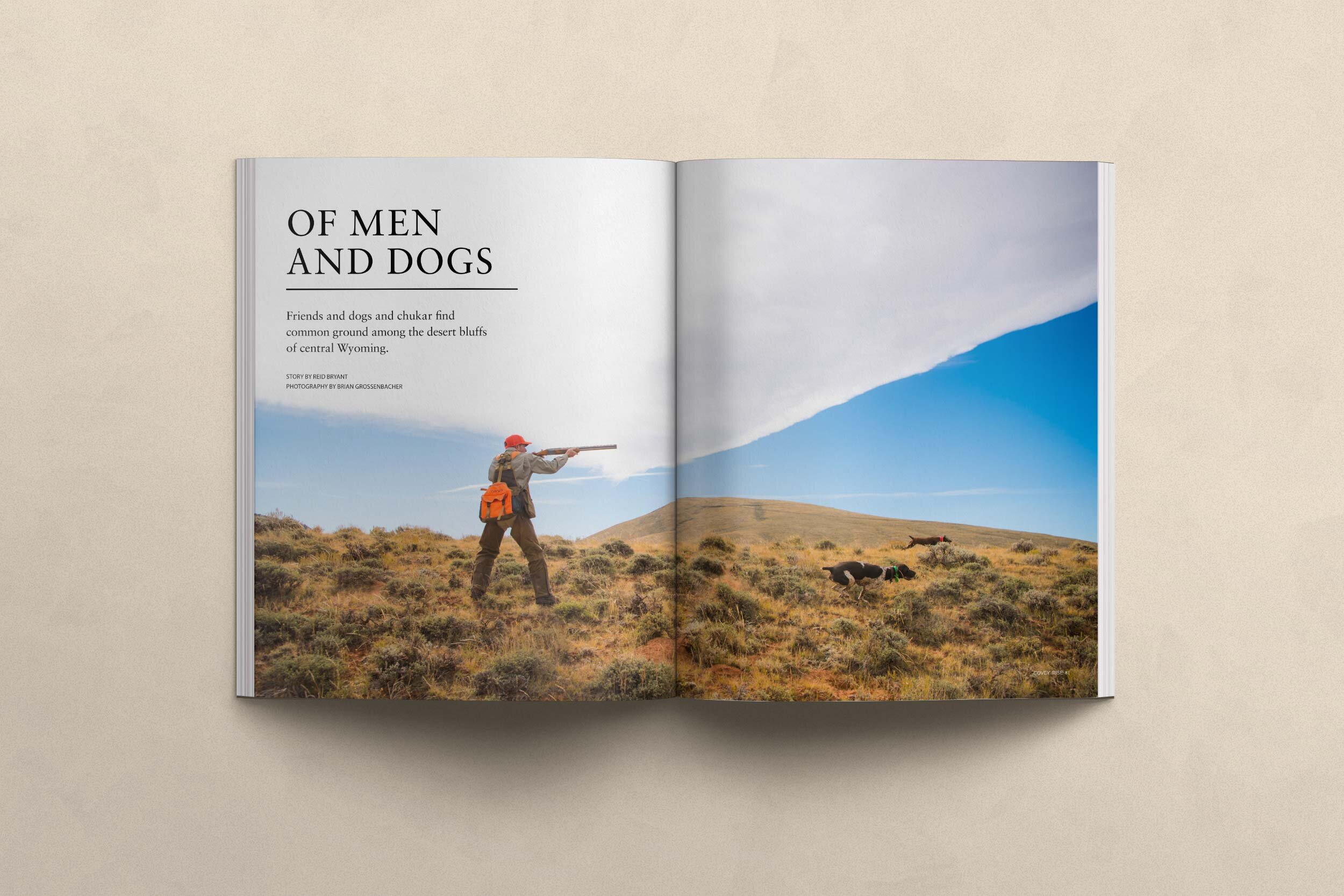

October just south of Lander, Wyoming, is a coincidence of ground and season that connotes cattle guards and pronghorns and wind. It is a space into which two bird hunters and a photographer can lose themselves or get lost, so big are the skies and the silences. That October, there was snow up high and cool air settling into the flats along Twin Creek, though the red of the bluffs seemed to radiate warmth, a relic of summer in sand and stone. The bottomland stretched out into sage and bunch grass and chert shards and soil, an archetype of western country that Robert Louis Stevenson once summarized with a sigh, writing “sage-brush, eternal sage-brush…” Against that, three men laced boots in the morning, at the mercy and the promise of the day.

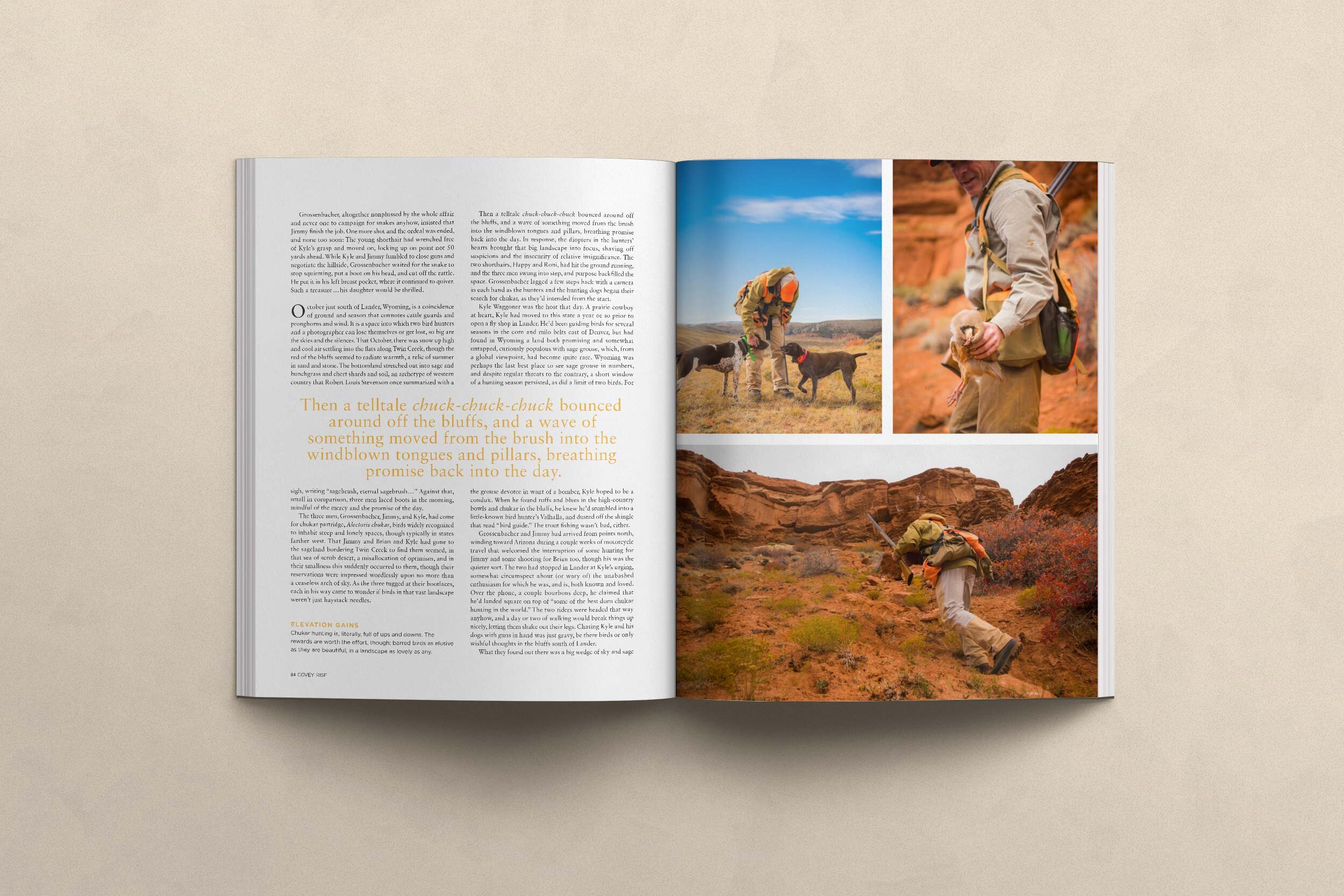

The three men, Grossenbacher, Jimmy, and Kyle, had come for chukar partridge, Alectoris chukar, birds widely recognized to inhabit steep and lonely spaces, though typically in states further west. That Jimmy and Brian and Kyle had gone to the sage-land bordering Twin Creek to find them seemed, in that sea of scrub desert, a misallocation of optimism. As the three tugged at their boot laces, each in his way came to wonder if birds in that vast landscape weren’t just haystack needles. Then a telltale chuck-chuck-chuck bounced around off the bluffs, and a wave of something moved from the brush into the windblown tongues and pillars, breathing promise back into the day. In response, the diopter in the hunters heart brought that big landscape into focus, shaving off suspicions and the insecurity of relative insignificance. The two shorthairs, Happy and Roni, had hit the ground running, and the three men swung into step, and purpose backfilled the space. Grossenbacher lagged a few steps back with a camera in each hand as the hunters and the hunting dogs began their search for chukar, as they’d intended from the start.

Kyle Waggoner was the host that day. A prairie cowboy at heart, Kyle had moved to this state a year or so prior to open a fly shop in Lander. He’d been guiding birds for several seasons in the corn and milo belts east of Denver, but had found in Wyoming a land both promising and somewhat untapped, curiously populous with sage grouse, which, from a global viewpoint, had become quite rare. Wyoming was perhaps the last best place to see sage grouse in number, and despite regular threats to the contrary, a short window of a hunting season persisted, as did a limit of two birds. For the grouse devotee in want of a bomber, Kyle hoped to be a conduit. When he found ruffs and blues in the high-country bowls, and chukar in the bluffs, he knew he’d stumbled into a little-known bird-hunter’s Valhalla, and dusted off the shingle that read “bird guide”. The trout fishing wasn’t bad either.

Grossenbacher and Jimmy had arrived from points north, winding towards Arizona on a couple weeks’ worth of a motorcycle trip. The two had stopped in Lander at Kyle’s bequest, somewhat circumspect of the unabashed enthusiasm for which he was, and is, both known and loved. Over the phone, a couple bourbons deep, he claimed that he’d landed square on top of “some of the best durn chukar hunting in the world.” The two riders were headed that way anyhow, and a day or two of walking would break things up nicely, letting them shake out their legs. Chasing Kyle and his dogs with guns in hand was just gravy, be there birds or only wishful thoughts in the bluffs south of Lander.

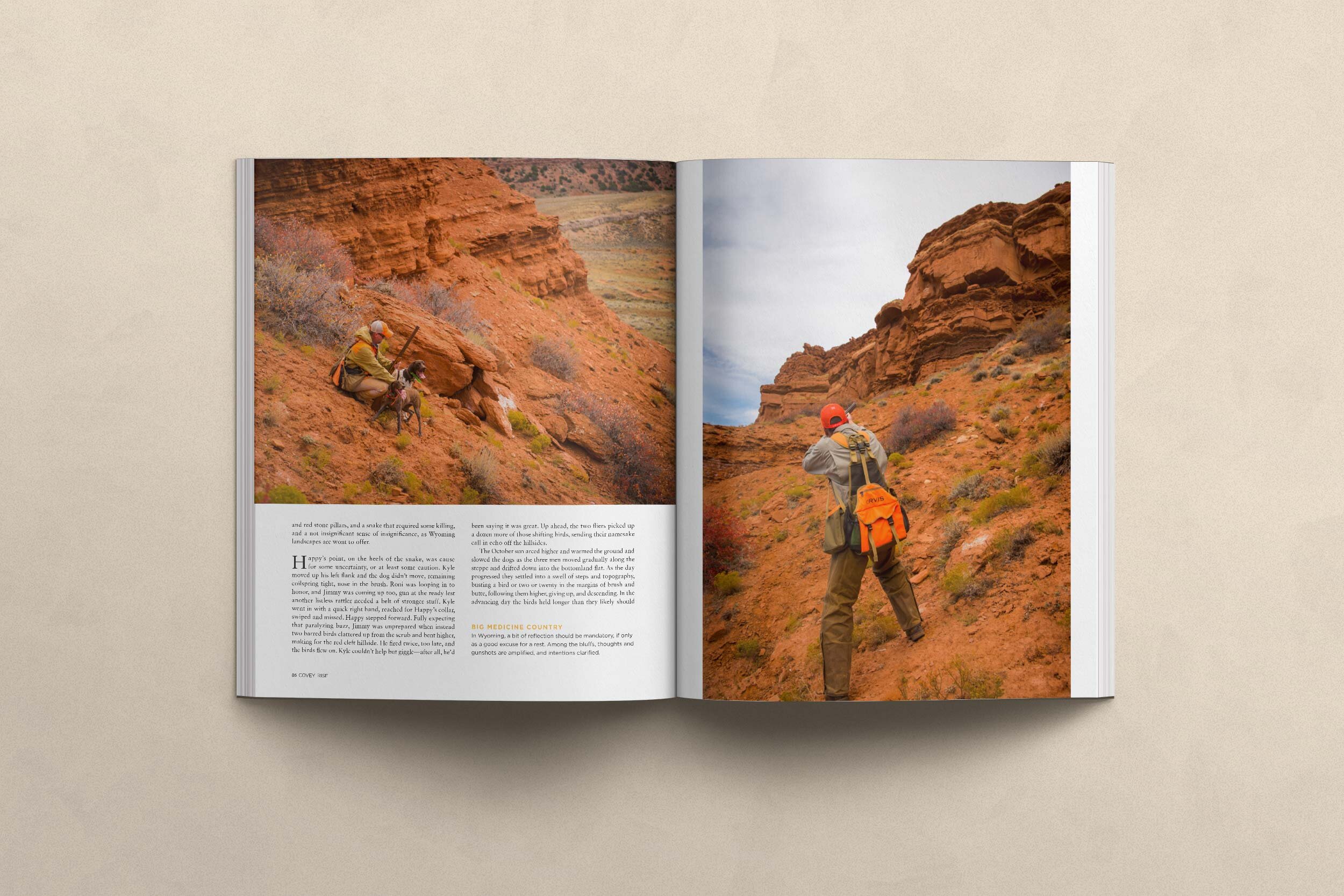

What they found out there was a big wedge of sky and sage and red-stone pillars, and a snake that required some killing, and a not insignificant sense of insignificance, as Wyoming landscapes are wont to offer.

*

Happy’s point, on the heels of the snake, was cause for some uncertainty, or at least some caution. Kyle moved up his left flank, and the dog didn’t move, and remained coilspring-tight, nose in the brush. Roni was looping in to honor and Jimmy was coming up too, gun at the ready lest another listless rattler need a belt of stronger stuff. Kyle went in with a quick right hand, reached for Happy’s collar, swiped and missed. Happy stepped forward. Fully expecting that paralyzing buzz, Jimmy was unprepared when instead two barred birds clattered up from the scrub and bent higher, making for the red cleft hillside. He fired twice too late, and the birds flew on, and Kyle couldn’t help but giggle. He’d been saying it was great after all. Up ahead, the two fliers picked up a dozen more of those sifting birds, sending their namesake call in echo off the hillsides.

The October sun arced higher and warmed the ground and slowed the dogs as the three men moved gradually along the steppe, and drifted down into the bottomland flat. As the day progressed, they settled into a swell of steps and topography, busting a bird or two or twenty in the margins of brush and butte, following them higher, giving up and descending. In the advancing day the birds held longer than they likely should have, and Happy and Roni caught them leaning, and held. A precious few made for easy shooting, but the hunters, weary from the walking, managed some of those lovely composed shots that only come when cognition gives way, and the swing is unthinking and true and nearly an afterthought, and shot and bird collide. Gray birds with barred flanks slowly filled the game bags, and water from the bottles conversely lightened the load, slopping over the muzzles and lolling tongues of the dogs. Nearing day’s end Roni went on point once more, and the hunters clamored up a ribbon of loose soil, found a semblance of footing, and caught their breath. Grossenbacher was right there behind them. As the two moved in, he was at Jimmy’s hip and a wee bit back, anticipating a bird and dog and hunter suspended in the frame, a trinity of sport and a moment of uncluttered intention. It was then that the wind up the canyon washed the sage and the bunch grass, and hit the folds in his sweat-stained shirt just right, and fluttered them, quickly moving the now-forgotten rattle in the left breast pocket. To hear Grossenbacher tell it he damn near suffered a coronary then and there, squealed like a schoolgirl and all but ran up Jimmy’s back, altogether unaware of the birds that broke free and soared off unnoticed and untouched. “I didn’t know whether to take a shit or wind my watch,” he’d later say, articulating his panic in cowboy vernacular, which somehow made it seem even funnier, though I’m sure, at the time, not to him.

*

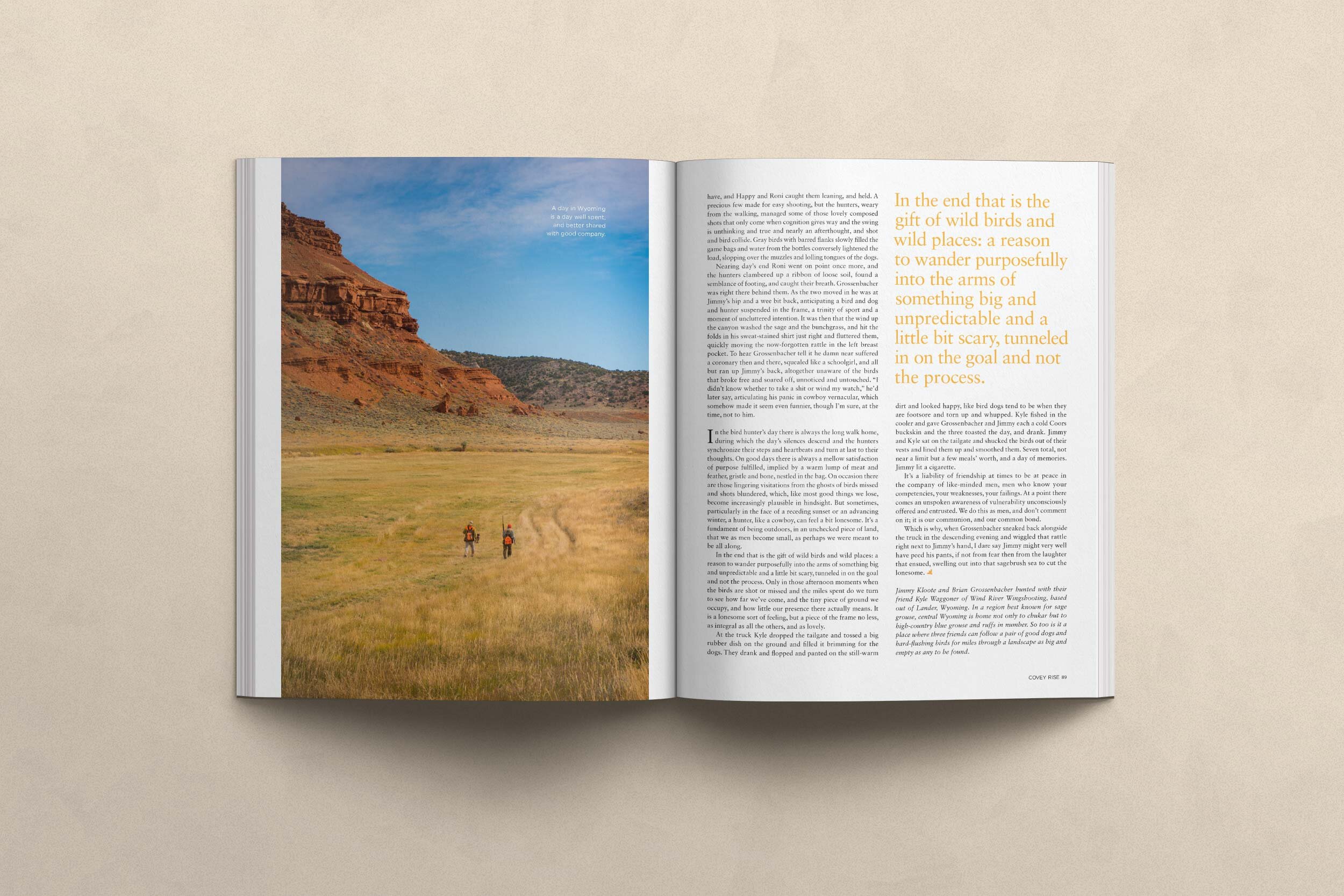

In the bird hunter’s day, there is always the long walk home during which the day’s silences descend, and the hunters synchronize their steps and heartbeats and turn at last to their thoughts. On the good days, there is always a mellow satisfaction of purpose filled, implied by a warm lump of meat and feather, gristle and bone, nestled in the bag. On occasion there are those lingering visitations from the ghosts of birds missed and shots blundered, which, like most good things we lose, become increasingly plausible in hindsight. But sometimes, particularly in the face of an advancing sunset, in the face of an advancing winter, a hunter, like a cowboy, can feel a bit lonesome. It’s a fundament of being outdoors, in an unchecked piece of land, that we as men become small, as perhaps we were meant to be all along.

In the end, that is the gift of wild birds and wild places; a reason to wander purposefully into the arms of something big and unpredictable and a little bit scary, tunneled in on the goal and not the process. Only in those afternoon moments when the birds are shot or missed and the miles spent do we turn to see how far we’ve come, and the tiny piece of ground we occupy, and how little our presence there actually means. It is a solitary sort of feeling, but a piece of the frame no less, as integral as all the others, and as lovely.

At the truck, Kyle dropped the tailgate and tossed a big rubber dish on the ground and filled it brimming for the dogs. They drank and flopped and panted on the still-warm dirt, and looked happy, like bird dogs tend to be when they are foot-sore and torn up and whupped. Kyle fished in the cooler and gave Grossenbacher and Jimmy each a cold Coors buckskin, and the three toasted the day, and drank too. Jimmy and Kyle sat on the tailgate and shucked the birds out of their vests, and lined them up and smoothed them. Seven total, not near a limit but a few meals worth, and a day of memories. Jimmy lit a cigarette.

It's a liability of friendship at times to be at peace in the company of like-minded men, men who know your competencies, your weaknesses, your failings. At a point there comes an unspoken awareness of vulnerability unconsciously offered and entrusted. We do this as men, and don’t comment on it; it is our communion, and our common bond.

Which is why, when Grossenbacher snuck back alongside the truck in the descending evening and wiggled that rattle right next to Jimmy’s hand, I dare say Jimmy might very well have peed his pants, if not from fear then from the laughter that ensued, swelling out into that sage -brush sea to cut the lonesome.

First Published in Covey Rise